Last updated on October 29th, 2025

In Applied Behavior Analysis, tracking behavior helps therapists understand progress and make treatment decisions. One crucial way to do this is through a measurement system. These systems show how often or how long a behavior may occur. There are two main types of measurements, i.e., continuous and discontinuous.

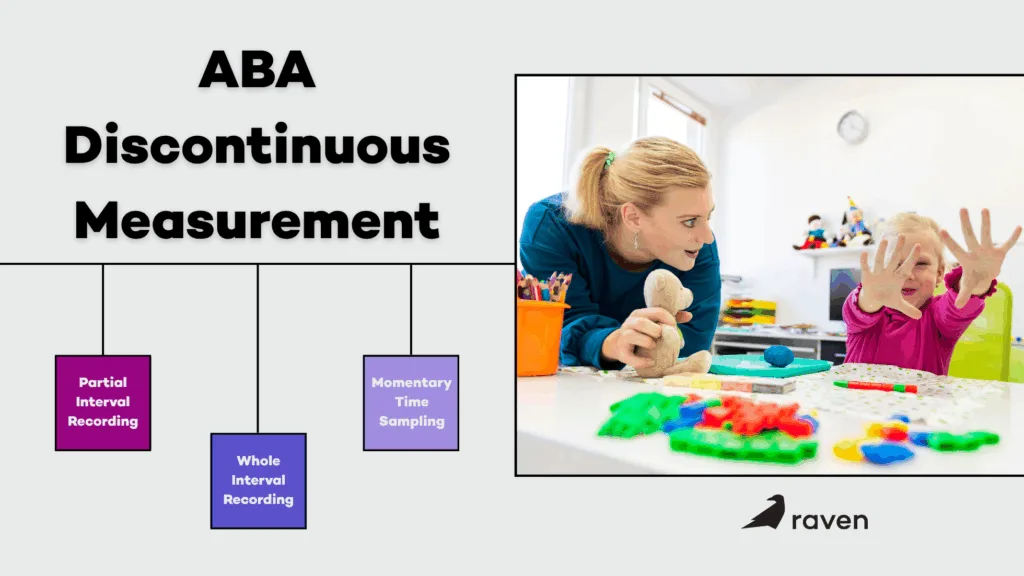

This article focuses on discontinuous measurement, how it differs from continuous measurement, its types, when to use each, and their advantages and limitations.

What is Discontinuous Measurement?

Discontinuous measurement is a data collection method used in ABA where the observer records behavior at specific moments or within set time intervals, rather than tracking every single occurrence. Instead of capturing the full picture, it provides a sample of the behavior across time.

In simpler terms, you divide the observation period into equal chunks of time (called intervals) and check whether the target behavior happens during those intervals. Depending on the method, you may record:

- If it happened at any time in the interval (Partial Interval),

- If it happened the whole time (Whole Interval),

- Or if it happened exactly at a specific moment (Momentary Time Sampling).

This approach gives you a general estimate of how often or how long a behavior occurs without needing to observe continuously

Discontinuous Measurement VS Continuous Measurement

1. Continuous measurement

With continuous measurement, You record every instance of the behavior, and its precise start and stop times (frequency, duration, latency), so you get a complete record.

2. Discontinuous measurement

With discontinuous measurement, You observe behavior during set time segments (intervals) and record whether the behavior occurred (or occurred at the moment) during those segments. You do not capture every occurrence or exact duration.

| Factor | Continuous Measurement | Discontinuous Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Precision (Level of Detail) | Records every instance, start/stop times, durations, and exact counts. | Samples behavior across time; provides an estimate rather than a complete record. |

| Workload for Observer | High—requires continuous attention and often a dedicated observer. | Lower—easier to collect while performing other tasks or supervising multiple people. |

| Best Uses | Low-frequency behaviors, safety incidents, latency/duration measures, and detailed functional analysis. | High-frequency behaviors, group monitoring, quick checks, or busy settings like classrooms or community outings. |

| Types of Data Produced | Exact frequency, total duration, inter-response times, and precise latencies. | Proportions or percentages of intervals or moments when the behavior occurred. |

| Accuracy for Short Events | High—captures brief events accurately. | Variable—may miss or overcount short events depending on interval type. |

| Training Required | Moderate to high—requires learning precise timing and operational definitions. | Moderate—focuses on interval timing and scoring rules; easier to master. |

| Interobserver Reliability (IOR) | Can be high with proper training; easier to compute exact agreement for events. | Can be good with training, but timing errors or differing interpretations can reduce consistency. |

| Equipment or Tech Needs | May require timers, event-recording apps, or continuous video for later review. | Often just a timer or interval app; works well with simple checklists. |

| Sensitivity to Change | High—detects small shifts in frequency or duration. | Lower—captures trends but may miss small or rapid changes. |

| Data Analysis Complexity | More complex—requires processing large datasets for graphs and analysis. | Simpler summaries like percentages or trend lines; ideal for quick reports. |

| Use for Decision-Making | Best for precise decisions that affect treatment (e.g., safety or reduction goals). | Useful for monitoring trends and identifying increases or decreases in behavior. |

| Ideal Observation Length | Suitable for any session length, especially when full documentation is needed. | Works best for short-to-moderate sessions (5–30 minutes) or repeated observations throughout the day. |

| Risks When Used Improperly | Risk of observer fatigue and missed events due to lapses in attention. | Risk of misrepresenting behavior levels if interval timing or training is poor. |

| When to Validate with the Other Method | Use continuous measurement to validate discontinuous data periodically (spot-checks). | Use discontinuous measurement for daily tracking, validated occasionally with continuous data. |

| Example Settings | Functional analysis sessions, safety monitoring, and precise research studies. | Classroom tracking, clinic groups, community programs, and large-scale behavior screening. |

Types of Discontinuous Measurement

1. Partial Interval Recording

What it is:

Divide the observation period into equal short intervals (for example, 10 seconds). Mark the interval if the target behavior occurred at any time during that interval.

How to do it:

- Decide total observation time (e.g., 10 minutes).

- Choose interval length (5–30 seconds is common).

- For each interval, mark “yes” if the behavior happened at least once; mark “no” if it did not.

- At the end, calculate the percentage of intervals with the behavior (intervals with behavior ÷ total intervals × 100).

When to use it:

High-frequency behaviors (e.g., hand flapping, vocal scripts) where counting every occurrence is impractical. Also, when you want to be conservative in detecting presence (it usually overestimates how much of the interval the behavior occupied).

For example, if behavior occurs briefly in 6 of 10 intervals, the score = 60% but the actual time engaged might be only 10–20% of the observation period.

2. Whole Interval Recording

What it is:

Whole interval recording divides time into equal intervals. You mark an interval only if the behavior occurs throughout the entire interval.

How to do it:

- Set total observation time and interval length.

- For each interval, mark “yes” only if the behavior was present the whole interval; otherwise, mark “no.”

- Calculate the percentage of intervals fully occupied.

When to use it:

For behaviors you want to increase (e.g., on-task behavior, engagement). Useful when measuring continuous engagement rather than brief bursts. For example, if a student is on-task for the full 4 of 10 intervals, score = 40%, even if they were partially on-task in more intervals.

3. Momentary Time Sampling (MTS)

What it is:

Observe at predetermined moments (the end or start of each interval) and record if the behavior is occurring exactly at that moment.

How to do it:

- Choose interval length and moment (commonly the end).

- Observe, then at the moment, and mark if behavior is happening at that instant.

- Calculate the percentage of moments where behavior was present.

When to use it:

When continuous monitoring isn’t feasible, but you want a quick estimate. Works well for overall trends across observers. For example, in a 30-minute observation with 30 one-minute intervals, you take 30 “snapshots.” If behavior is present at 12 snapshots, score = 40%.

When is Discontinuous Measurement Most Useful?

- High-frequency behaviors that would be hard to count accurately (e.g., repetitive movements, vocalizations).

- Settings with limited observers, like classrooms or community outings, where staff can’t continuously record.

- Large-scale monitoring to detect trends across many students or clients.

- Interim checks during baseline or large-group interventions when quick data is needed.

Advantages Of Discontinuous Measurement

- It is feasible in everyday settings, hence resulting in less observer fatigue.

- Efficient for frequent behaviors and group observations.

- Discontinuous measurement is useful for trends; for example it is good for showing whether behavior is going up or down over time.

- This type is easy to train staff on since it has straightforward rules and simple scoring.

Limitations Of Discontinuous Measurement

- It is less precise than continuous methods and therefore doesn’t capture exact frequency or duration.

- Discontinuous measurement can over- or underestimate true behavior level depending on method and interval length.

- Its longer intervals reduce accuracy.

- Also, interobserver reliability (IOR) can drop if observers aren’t well trained on timing and definitions.

Practical Tips for Reliable Use

- Keep intervals short (5–15 seconds) for fast behaviors; longer intervals for slower ones.

- Train observers with video practice and check IOR before collecting real data. Aim for ≥80% agreement.

- Run occasional continuous sessions to validate your discontinuous data.

- Be consistent: same interval length, same observation times, and clear operational definitions.

Conclusion

Discontinuous measurement is a practical, widely used option in ABA when continuous recording is impractical. Pick the method that matches your goals: partial interval for detecting frequent behavior, whole interval for measuring sustained behavior, and momentary time sampling for quick snapshots. Always watch the limitations and use training and periodic checks to keep your data trustworthy.